A Great Tool for Creating Mood Boards – sampleboard.com

April 20, 2011

In a number of other posts I have discussed mood boards, concept boards, storyboards, journey boards, etc. In most of those posts I mentioned PowerPoint and similar graphics programs as excellent tools for creating them. Last year I became aware on an extremely good online tool that addresses the needs of many different design professionals, sampleboard.com (www.sampleboard.com).First, in addition to creating boards for landscape designers, sampleboard.com can be used by interior designers, graphics and web designers, fashion designers, and wedding planners. Second, you can use it for free without registering. By registering though, you are able to save and share your boards. There are also paid plans with additional features.

To begin, you select your paper size. Unfortunately, no standard US sizes are available. Then you pick the type of board you want to create such as landscape design. On the right of the screen are a number of filters that allow you to pick from the sampleboard.com gallery of images. Categories include hardscape, softscape, garden decor, and others. Within these categories are types. Hardscape types would obviously be different from softscape types. Below that there are additional filters for Type, Style, and Supplier. Once you set the filters there are one or more windows of choices for you to review. Placing your mouse pointer over the thumbnail image choice brings up a larger preview display. When you find an image that is appropriate for the board you are creating, you simply drag it to the design board.

Once it is on the design board you can size and position it. As you add components to your board you can switch from category to another. You might add Hardscape design elements and then move on to Softscape and Garden Decor.

Sampleboard.com also has very good layout, drawing, and editing tools. You can use the Magic Eraser to pull the background out of an image. You can move objects forward and backward to layer them. There are other Photoshop-like tools that you can use to modify the various images you add to your board. Also, there are tools for adding shapes and text to your board and you can color these as you see fit. Another plus is you can paste images from other sources.

The graphic below is a sample mood board created on sampleboard.com.

If you would like to see more samples check this post in the sampleboard.com blog, Garden Ideas – Select your Garden Theme or Garden Style.

Sampleboard.com is very useful. It has a lot of very powerful capabilities built into it. I find that fact that it is online to be very useful. If I am working in the field on a tablet computer I can access sampleboard.com and compile ideas. I don’t need any other software to get started. Also, any pictures I take with the table can be pasted directly onto by board as part of the ideation process. I also find it is useful for marking up site pictures for a site analysis.

I suggest checking out sampleboard.com and bookmarking it for future use.

Client Benefits – A Tool for Validation

October 31, 2010

The ultimate in validation would be measurable benefits for your client when the project is done. What would those benefits be? How do you measure them? What are the measures? I am not talking about cost/benefit analysis. Landscape design is too esoteric for that. Too many benefits are intangible. You may save the client money with your design approach or reusing materials, which certainly are benefits, but that is not the type of benefit I am referring to.

Let’s start with a classic client interview question. “What will be different, better, etc. when your landscape project is complete?” Your client can give you a multitude of answers. Most of us ask this question seeking to identify client needs. If we know what the client wants to be different or better, we have defined a need that can be addressed. But is there anything in the client’s response that is measurable? Is there a benefit we can measure and track to show how we improved it for the client?

When I stop and think about this question I think there are things you could measure. If a client asks for a quieter space, you could do ambient sound measurements before and after. If a client asks for more entertaining space you could measure the space pre and post project. But are these examples really the benefits we are looking for? If I could measure the client’s satisfaction with their outdoor space when I first interview them and then measure it again after the design and install is complete, I would have a valid measurement of the increase in their satisfaction. Unfortunately, satisfaction measures are intangible. Getting rave reviews from the client is great validation but you are relying on your design to come through and for the client to actually give you those kudos.

There is a benefit for you in thinking about your client’s benefits at the beginning of a project. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples. Assume the client is complaining of a lack of shade in their current entertaining space. During your site analysis you could do some calculations and measurements and determine that the existing space has ninety square feet of shade on an average day between May and August. If your design increases that, you have the data to present to the client during the design review that your design increases the entertaining space shade from ninety to one hundred seventy square feet, almost doubling it.

Another example might be an unsightly view. Depending upon the circumstances you may be able to say that you were able to partially or fully obscure it with your design. There are other ways to handle this. First, a digital photo of the current view can be overlaid with a drawing showing the fence, softscape, or whatever approach you are using to obscure it. With 3D design software you would be able to pan around the area and show the client the new view.

Having benefits that you can address gives you an opportunity to use the Feature / Function / Benefit approach in your proposal. Addressing many specific benefits may also allow you to be more aggressive in your pricing.

This comes back to the real fundamental issue, validation is making sure that client needs are addressed in the design. Having a design objective that is a benefit for the client, and preferably one that is measurable, makes validation even easier.

Bubble Diagrams – A Useful Step in the Validation Process

October 25, 2010

Bubble diagrams are a useful design and analysis tool. They help us understand space adjacency, layouts, and relationships, traffic flows, and relative space sizes among other things. They are a visual tool for representation. We can use them to help us understand aspects of the design problem we are trying to solve without investing huge amounts of time with complex and detailed drawings. They can also be useful for ideation.

As a general rule, bubble diagrams are created after space adjacency analysis. There should be one bubble for each space listed on the adjacency analysis. The lines connecting those bubbles or the lack of lines are the depiction of the results of the space adjacency analysis. Dark, heavy lines represent close or high adjacency, dashed lines may represent some adjacency, and no line obviously represents a lack of adjacency. Sometimes in may be useful to actually sketch out a bubble diagram to help think through the space adjacency analysis. Seeing the spacing represented as bubbles may help you to think through the relationships between spaces and make decisions as to how strong or weak the adjacency should be.

There are other things you can do with a bubble diagram to make it more useful. You can draw them on top of a copy of the base plan. This will give you some preliminary ideas about how the spaces will actually fit into the area you have to work with. As mentioned previously making the bubble sizes larger or smaller to show the amount of relative space each will require is useful. You just have to remember that the actual space layout is not likely to be a circle. I have mentioned another technique in a previous post [Thumbnail Bubble Diagrams – A More Complete Portrayal] where you place a graphic such as a picture or drawing inside each bubble to represent what is actually going to be inside that space. This technique simply provides an additional layer of visual detail to help with your analysis of how the space will function together as a cohesive whole. It can also be useful if you are going to show the bubble diagram to the client for clarification or feedback.

With all of the potential benefits of bubble diagrams it is important to keep a couple of things in mind. First, there are a lot of “rules” dictating how bubble diagrams should be drawn. For example, no bubbles should touch or overlap. No line should cross another line or another bubble. These constraints are intended to make sure your bubble diagram makes sense logically and that the spaces flow or connect in a consistent manner. It does not mean that your design implementation will follow those rules.

Second, the bubble diagram is a design and analysis tool. As such you should validate you input into it’s creation and the output from how you use it. As stated above, the bubble diagram is usually based on the space adjacency analysis. You should use the space adjacency analysis to check off or validate that you have address every space and every adjacency and non-adjacency. The same applies going on to subsequent steps. You might do an overlay of your bubble diagram over various form compositions. That in itself is a validation process. The next most likely step is to create functional diagrams. Again you should make sure that your functional diagram carries forward the adjacencies and other relationships expressed in the bubble diagram.

Finding Design Freedom in the Space Adjacency Matrix

October 15, 2010

An important result from a space adjacency analysis is the linkages between spaces that you find. Spaces that are linked can often be treated as single units when you begin functional design or conceptual design. An equally important finding is the lack of linkages. White space in the adjacency matrix means design freedom; few constraints in how components can be arranged.

Imagine a client who wants a dining area, a conversation area, and a pool area. Within each of these spaces are sub-spaces. The dining area in this example is to have an outdoor kitchen and the table / dining area. The conversation area needs to include a large gathering space around a fire pit, a table for games or a small group, and a smaller more intimate area for more individual or casual use. The pool area must include the pool, pool equipment/storage space, lounging area, a cabana, and potentially other amenities such as a pool area kitchen/bar and outdoor showers.

The space adjacency matrix for this project would list the elements individually because they serve different functions. However, if you think about it, every component of the pool area is going to have high adjacency requirements with all other pool components because everything is associated with the pool. The conversation area with its three areas is also linked as are the dining area components. The space adjacency matrix will reflect these relationships:

What we are seeing is the interrelationships of the three areas and also a lot of white space. Large areas of white space in a space adjacency matrix usually mean a lot of design freedom to position and arrange the areas. On the surface you would think we are dealing with the relationship between three spaces not a dozen sub-spaces.

We could think about how we are going to functionally position and arrange these three spaces as large units. However, you cannot entirely eliminate the details of arranging the individual components either. There are a couple of issues to consider. First, one or more individual components of the large space may require special attention or have a negative adjacency relationship with the other spaces. A prime example of this is the pool equipment. We don’t want to position the pump, filter, and heater near the other entertaining spaces. If we update our adjacency analysis to reflect this, we can see that we still have quite of bit of white space to work with:

Second, you can perform space adjacency analysis within each of the larger components, but it is difficult to know how to functionally arrange those components without having an idea of the overall functional arrangement. The white space we are dealing with effectively represents the relationships between the three areas. Those areas need to adjoin one another in some form so they are contiguous. If we highlight our space adjacency analysis with the portions of the matrix that impact each of the three areas we get a better sense of how they are interrelated:

This becomes a chicken or the egg problem. It would make sense to work on the overall functional arrangement first and then deal with the functional arrangement within the individual space components. However, you still have to look for those negative relationships between the larger spaces that are created from the specific functional space components (i.e., the pool equipment). At a macro level we have three space adjacencies to deal with. Within each of those three spaces we have micro level adjacency issues. Those micro level issues impact the macro level.

The problem we have not considered at this point is the client’s preferences. In this particular example the three spaces each has the potential for having a fair amount of client preconception as to where the space should be. The pool is an obvious example of this. Many clients are going to want the pool prominently positioned so it is the first thing you see when you enter the space. A few clients may feel differently and want the pool away from the main entertaining area, visible, but not integrated into the other areas. Most clients are going to want the outdoor kitchen and dining areas near the house to facilitate food preparation and serving. The conversation area is probably less likely to be subject to predisposition unless there is a particular place in the area with a great view or attractive is some form or fashion. All of that white space gives us a high degree of functional design freedom within the constraint of how the client plans to use the space and how they see the space relationships.

Space adjacency analysis is not a science. There is a fair amount of logic and common sense in the process. You don’t put things next to each other that conflict. However, you have to also think about the adjacency from the standpoint of the client’s preferences and perceptions. As a designer you can figure out what makes sense and what does not. The art is in understanding how the client wants the space to feel, perform, and look. However, neither of these steps, logic or client preference, are mutually exclusive. Nothing in the continuum between art and science precludes creativity.

When I first looked at this project the first thing I saw was the potential to integrate the outdoor kitchen with the pool area kitchen / bar. There is a lot of potential to not only save the client money but also create a dual function space that could actually be used independently or in tandem. As great as this concept might be it is subject to the client’s feelings and preferences regarding placements.

The link between validation and analysis is understanding and knowledge. We have to know what the client wants and we have to use our experience and knowledge to analyze the needs and make appropriate design decisions.

Space Adjacency Analysis Requires Understanding

October 11, 2010

The use of space adjacency analysis is more common in architecture than in landscape design. This is primarily because buildings are built to serve a purpose; to house a business operation or a functioning family. In the case of a business the building supports marketing, accounting, production, management, and other functional roles. Within every company the departments or functional areas interact with one another. Space adjacency analysis can facilitate the smooth operation of a company by optimally laying out the building space. An architect cannot do this effectively without understanding the relationships between the departments or functional areas. They need to know that sales and marketing work closely together, that production has to be isolated due to noise issues, and other interrelationships.

The saying form follows function is probably an apt description. Positioning various functional areas within a building requires understanding the necessary relationships between the areas (space adjacency analysis) and understanding how much space is required. Other factors come into play but understanding these basic things allows an architect to explore various configurations and layouts to meet the requirements. The functional layout may suggest various forms that can be applied to the building layout and design.

Space adjacency analysis as it applies to landscape design should also look into relationships of functional spaces. Understanding how a space is going to be used is necessary to develop the adjacency analysis. Simply saying that we have areas A, B, C, D, and E is not enough. We need an understanding of how the space will be used. A client who wants an outdoor kitchen for use in preparing family barbeques and entertaining friends and neighbors is one thing. A client who says “our kitchen is the heart of our home, we want the outdoor kitchen to be the heart of our outdoor space” is something completely different. A request for a seating area can mean many different things. Some clients may want a children’s play area close by and very visible in order to watch their children while other clients may want the space more distant to reduce noise and give adults some space of their own.

The point is that space adjacency analysis is driven by understanding the functions of each space and how those functions are related and how they may conflict. When thinking through a space adjacency analysis it is important to keep in mind that the space is outdoor living space. You have to understand how the client intends to use it. The client may have more than one purpose for a space. That is fine. You can treat each purpose as a functional area and look for adjacency issues. You will develop a better design by creating a layout that address all of the issues associated with every space. That only happens if you understand the functions of each space in your adjacency analysis.

The Design Parti – A Communication Tool

October 5, 2010

A concept that I have been intending to write about for some time is “parti”. A parti is usually a sketch, diagram, drawing, doodle, or some other graphic that represents the direction, concept, or theme of a design. The concept of parti is common in architecture. It is also used in other design disciplines. It is seldom mentioned in conjunction with landscape design however. That is part of the reason why I have not written about this concept until now. The other reason is that a parti is a vague concept.

A parti diagram does not necessarily represent what the design will look like when it is done. It is usually not a polished diagram. It can be very rough; the proverbial back of a napkin sketch. Parti has been defined as “the big idea”, “the central concept”, “the essence of the design”, “the design approach”, “the core element” and numerous other ways. In almost every case a parti is described as conveying the meaning, form, direction, essence, scheme, approach, or some other aspect of a design. If you are confused about what a parti actual is, I was too initially.

The first thing that was unclear is when in the design process a parti is actually created. The answer is that you create a parti after you have some analysis completed. You have to know where you have opportunities and where you have limitations. You have to know the client’s requirements. You should understand what functionality you need to provide. You should have created at least some bubble diagrams and prepared an adjacency analysis. In most cases a parti is going to come after some level of form composition analysis also. You may create several form compositions that you evaluate as potential starting points for your design. That being said, creating a parti comes after having a thorough understanding of the site, the client, and the functional and spatial aspects of your design.

The second confusing aspect of a parti was how it fit into the creative or generative portion of the design process. A parti is described as a vision and/or an inspiration. A parti is also shown as being a result or an output of one or more design concepts. Creating the parti comes after developing conceptual designs. Your source or inspiration for your conceptual designs may come from the site, the surrounding area, the client, the environment, or some other source. Your client may have a love of camping that leads you to develop a concept based on nature. The client residence may be of a Spanish style architecture that leads you do develop a Mediterranean theme concept. There a numerous possibilities.

So what exactly does a parti do? Why should you create one? I think a parti is a communication tool. It communicates the intent of your design concept. In A Visual Dictionary of Architecture (1995), Frank Ching defines a parti as “the basic scheme or concept for an architectural design represented by a diagram.” The parti should communicate something about the form as well as the concept. Ideally, your parti will communicate the experience you intend to create. It should depict something about the functional, sensory, and/or emotional aspects of your design concept.

I am not convinced a parti has to be a diagram or sketch. A picture, an object, maybe even a simple storyboard may serve the purpose of a parti. Which leads to the second question; why create a parti?

Anything that we can create that will make conveying our design intent to the client easier and more effective is a good thing. We all live in a world of headlines. We are flooded with information. We scan e-mails for important subjects. We skim newspapers for headlines. The 30 second sound byte is the norm. Imagine the power of a diagram or simple graphic that you can show the client and they will immediate see what you want to do. Maybe your plan view does that. Or maybe you created a perspective illustration that conveys everything the client needs to know. You may not need a parti in every design. However, if you can create one, it would certainly add value to your client presentation.

There is one very important difference in how and why a parti is used in architecture versus landscape design. In architecture the designer is working in a third dimension in creating a building or structure. That is not to say landscape design does not involve height or structural elements. The mass of a structure just does not impose upon our designs the way it does in building architecture. This is why I think our use or interpretation of a parti can be different.

As I said earlier, a small storyboard may be what you need to convey your parti. Maybe there was an object or something that you saw that inspired your design concept. A picture of that object may be your parti or a part of it. Maybe one of your form compositions can be modified to express more fully the design concept. Again, what we are looking for is a communication tool. The format or media does not really matter.

One last point about the value of a parti. I have read in several places that a parti should “anchor the design”. In other words, when a design issue or question arises, you should be able to go back to the parti for answers. In other posts I have mentioned the value of graphic tools such as a client profile, journey boards, inspiration boards, etc. to facilitate the design process. A parti can serve the same purpose. It communicates the intent of your design concept to your client. Having your parti in front of you while you are designing will serve as a constant visual reminder of your design intent.

Adjusting Bubble and Functional Diagrams for Usage

September 26, 2010

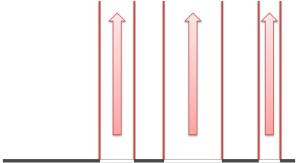

When creating bubble or functional diagrams it becomes important at some point to begin working in rough scale so you can understand proportions and space utilization. It is very easy if you are using diagramming software to make bubble diagrams or functional diagrams proportional.

Using PowerPoint as an example, you draw a rectangle four by two to represent forty by twenty feet or six hundred square feet (a one inch equals ten feet scale). When you create the bubble shapes you size them according to the required space. You can make any shape you want. You can pick the best shape to represent each area. You just need to scale it. In PowerPoint you would right click on the shape, select format shape, and set the size to represent the scale you need. For example, a circle representing a table that needs sixty three square feet could by a circle with a diameter of nine feet or .9 inches. If you want to use a square that is proportional you could make a square with sides of 7.95 feet or .795 inches. A rectangle would be set at .7 inches by .9 inches to represent the size.

The point of this is to emphasize an issue about scaling in bubble or functional diagrams. Do you use a proportionate size for the object itself or a size for the space the object requires when being used? A table is a good example. The table, with the chairs pushed in may be seven feet by nine feet. However, when guests are at the table sitting in the chairs the space requirement is more likely nine feet by eleven feet at a minimum. A grill is another good example. The grill itself may have a footprint of ten square feet. If you are using the grill during a party or dinner the space may easily double to allow for room to maneuver and to avoid the heat and smoke.

Given the fact that you are working from your adjacency matrix, the proximity or lack of proximity may well be important in how bubbles or functions are placed within the space. One technique that I use to help with this issue is to create a shape and then duplicate it in a larger size. The original shape represents the footprint of the space or object. The second shape represents the required footprint when it is being used. I then simply center these shapes on top on each other with the usage footprint on the bottom. For example, the diagram below shows the space for a table and chairs. The inner shape is the object footprint. The outer shape is the usage footprint.

Not every object may require extra space. You may also be able to adjust how the usage footprint relates to the object footprint. For example, the functional diagram below shows the lounging area has the same usage footprint as the space itself. The grill foot print extends out to the front and to the left side since the back and right side of the grill are at the edge of the space.

Showing the buffer area that will be utilized when the space is being used allows you to make adjustments that are needed due to space adjacency requirements. Also, this is extremely useful in planning traffic flow, overall space utilization, and space allocation.

There is some additional work in going to this level of detail but it is fairly minor. As long as you establish your scale in the graphic program you are using and work out the areas required for each functional area most graphic programs make it easy to scale the functional objects. The effort may help you uncover a potential problem long before you ever get to the design stage.

Bubble diagrams are a great tool for ideation, adjacency analysis, and space planning. In a previous post I stated that I think functional diagrams are a more formal tool to explore how spaces will fit together and get a better sense of potential design layouts and patterns. Bubble diagrams are the rough tool. Functional diagrams are a more precise tool.

In making the transition from bubble diagrams and functional diagrams it is useful to have some idea of form composition. Are you going with a rectangular, diagonal, arc and tangent, etc.? Having an overlay of the base plan that is marked with the various lines of force that you want to evaluate can be useful for building your functional diagrams.

Consider this example. The owners have a barren back yard. They want 600 square feet of outdoor space that accommodates a table for dining, a conversation area with a fire pit, a lounging area, a grill, and a water feature. The space is open off of a sliding glass door. There are windows on each side of the sliding door. Shown below are to base plans with lines of force marked for rectangular and diagonal form compositions.

In the rectangular form composition there are only lines running out from the back of the house at the door and window openings. However these three openings suggest a pattern extending from the back of the residence. The diagonal form composition has twice as many lines since they run in both directions. My take on this pattern is that the two lines extending from the door opening have the most potential. My decision is to go with the rectangular form composition because of the three major lines extending from the back of the house.

The bubble diagram I prepared reflects the results of the space adjacency analysis I performed. The water feature should be visible from the table, conversation area, and lounging area. The table should be accessible from the grill and the house. The grill should not be overly close to the house, table, lounging area, or conversation area.

At this point I am ready to see how the bubble diagram interfaces with my form composition. I am using PowerPoint in this case, so I simply copy one on top of another:

Everything seems to line up but this may not be the optimal placement. That is really the point I am trying to make about the difference between bubble diagrams and functional diagrams. I want to explore placement of spaces within the form composition to determine my final design layout, spacing, and placement. The bubble diagram was a rough tool. It helped me establish adjacency relationships. I need to go a step further and begin placing functions within the space. The diagram below shows how the functional “bubbles” were generally placed.

The lounging area is positioned to the right since that area offers the best sun exposure and it is less likely to interfere with the grill. The table and conversation area were positioned to the right, away from the grill. The table is closer to the door. The lounging, conversation, and table areas all have visual contact with the water feature.

The next step is to create the actual design pattern for the space and to physically position the areas more precisely. This is the final design. The two side pieces build off the lines of force from the windows and also push the lounging area and conversation areas further away from the house. The water feature makes a nice focal point and is centered on the lines of force from the door.

Using overlays to check patterns and explore ideas is easy. DynaSCAPE can be used to create the base plan which can be exported to PowerPoint, Photoshop, or a similar program. Even scanned images can be used. Use may have to remove the white background color since overlays tend to work better if they are transparent.

Using analytical tools and techniques is all part of the validation process. The preliminary bubble diagrams were based on adjacency analysis of the required spaces. These were overlaid on to base plans for form composition analysis. Finally the selected form was overlaid with a functional diagram to identify the placement and relationship of the spaces. These preceded the preliminary design and final design. Going through these steps helped assure that the design was appropriate and met the client’s requirements.

How Many Designs Do You Create for a Client?

September 10, 2010

An interesting post in the Designers on Design blog today titled “Plan B“. The thrust of the post by Danilo P. Maffei, APLD, is that only one design should be created for the client; there is no need for a backup plan if you know the first or primary plan is your best work and it is the right design for the client. His argument is that not only does it take more time; it also makes us less committed to the success of our primary plan. There are several interesting follow-up comments to the post. The post and comments are well worth reading.

I believe the best approach is to have one single final design unless the client specifically asks for multiple designs and is willing to pay for them. In this case, each plan should meet the same criteria in terms of meeting the client’s requirements. Serving up two completely different designs that meet the same requirements means a substantial amount of additional work in terms of validating that each design provides the same functionality and meets the client’s needs. The only way this could vary is if the client asked for two or more plans that provided different functions or were based on different budgetary or time constraints.

If there is a need for experimentation or consideration of alternatives, that should come during pre-design. Frequently during the ideation phase I work through iteratively. Based on some usage scenarios I try to understand the adjacency requirements and prepare a few bubble / functional diagrams. Then, I will shift gears and start looking at potential form compositions. After generating some ideas I will go back to my bubble / functional diagrams and see how they work within the form composition ideas I have generated. I may start looking more closely at traffic flow or other issues. Two or three of these ideas may be worth pursuing in more detail and may be considered as potential starting points for preliminary designs. Preparing more than one preliminary design is acceptable and may be worthwhile from the standpoint of validating the client’s requirements.

The point of design validation is to make sure that all of the alternatives, choices, and issues are resolved before the final design is completed. Completely validating a design implies that the one and only final design meets the client’s needs. It should match the client’s style and tastes. It should include the hardscape and softscape elements that the client prefers or will be happy with. If the design has been fully validated there should be no need for a Plan B.

What if Design Validation Doesn’t Work?

August 22, 2010

What happens if your design validation efforts do not produce an acceptable design. How do you deal with a situation where your design misses the mark; the client does not like it or they don’t think it will work for them. Everything I have been put forward in this blog has been focused on making sure you understand the client, knowing what they want and need, analyzing the data, and making sure you are focused on what really needs to be done. What if the client is not impressed and just outright says it is not what they want? How do you recover? Can you recover? What went wrong?

Following a design process increases the likelihood of success but it does not guarantee it. The design validation process requires you to do your due diligence and ask questions, research, analyze, evaluate, synthesize, and draw conclusions that lead you to a design concept. It does not guarantee that the design concept is correct or will be accepted. It is still possible to have miscommunications with the client. It is possible to misunderstand. It is even possible that the design concept is just wrong. It is more likely that something else is going on, which I will come to below. A major component of the design validation process is client communication. Involving the client early and often avoids surprises and disappointments at the end.

I tend to think clients reject a design for one of three reasons. First, something happened. The client lost their job or has some other financial emergency and they want to cut their expenses. Second, the client has buyer’s remorse and wants to step back and rethink what they are doing. Third, they truly don’t like what you created or do not think it will work.

In the first case, you may have some clue if something happened. There may be cases like the current economic situation where everyone is cutting back. If you suddenly find the client is available at any time of day, that may indicate they lost their job or something else is going on. All you can really do is be honest with the client. Ask them if something happened or if there was a change in their situation. You can point to all you have done for them and say that you have made a good faith effort to understand what they want and tried to design something that would meet their needs. Depending on the client, this may or may not work.

Buyer’s remorse is much harder to deal with. You have to sense this as an issue. If you have followed the process and have all of your documentation, you can walk the client through your findings. You can point to what they said, what you found, how your evidence supports that the design will meet their needs. You have to resell the concept and support it with what they said and what you found. Sometimes this works and sometimes is does not. Having good client management and people skills helps. You have to be empathetic and understanding but you have to drive home your findings and what you have done to validate your work. Again, constant communications with the client over the course of the project should have headed this issue off. Pre-design review of the design program and preliminary designs should also help curtail this problem.

In the last case where the client truly does not like the design and you have no other evidence to indicate any other issues, you have to find out what went wrong. There are many ways this situation can play out. If the client really feels your design is totally off base they may be angry and feel you have wasted their time and money. Occasionally a client may feel remorse that there was something they didn’t convey to you or that they didn’t give you enough guidance. The first step in understanding what went wrong is to deal with the current state of the client. If they are angry, you may have to let them cool down. The only way to find out what does not work in the design is to talk through it.

To talk through the design you have to go back to your basic interviewing and questioning skills. You need to find out what the client does not like or what they think will not work. If you have done all of the background research and analysis you can most likely argue any point they raise. However, you don’t want to get into an argument. What you are looking for is a way to modify the design so that it is acceptable or to help the clients convince themselves that the design is right. Many times the client is too close to their own situation to see what they really need. They may have asked for something directly or indirectly without realizing it and when you provided it, they were taken off guard.

There are many permutations of things that can happen, how clients will react, how a follow-up discussion will go, etc. It is easier to avoid the situation in the first place. There is nothing you can do about a change in the client’s financial situation. However, you can head off buyer’s remorse and head off clients rejecting your design by following the validation process and maintaining regular client contact and communication.

3D Visualization is the Key to Phased Designs

August 15, 2010

Phased approaches to landscape design are fairly common. In today’s economy they are more common. What they usually refer to though is doing one area at a time, and going year by year, to complete an entire yard or landscape. With this approach the backyard, or entertaining space, is usually first. The front yard, adding curb appeal is usually second. Any remaining areas are done at the end. From the designers perspective this works well because you focus on one area at a time and move on from one space to the next. Assuming you do a good job, you have repeat business. However, from the client’s perspective this approach may have some disadvantages.

First, doing the backyard entertaining space first is usually the most expensive phase. Granted there are benefits of having a completed entertaining space. However, ignoring the front yard and curb appeal does not add to the value of the client’s residence. The client, in many cases, would be better served by spreading the design program out with a combination of changes that add value and meet long-term entertaining and livability goals. There are challenges to this approach though.

First, you have to understand the client’s budgetary constraints in terms of total expenditure and year-to-year expenditure. Knowing that will tell you what you have to work with in total and for any given year. The second challenge is in allocating the budget into spaces and components that will add value and provide the client with some immediate usable improvements. A third issue is that the setup for future improvements may leave areas incomplete, barren, or in a “under construction” state. What was and is a landscape design project is now also a multi-year project encompassing value management, client expectation management, construction management, and a number of other issues.

Managing a client’s expectations and setting priorities is difficult enough in a single space. When you are spreading work out over multiple areas and the client has to make choices about what is going to be done this year versus next year and the year after in multiple areas it becomes even more difficult. Even worse is getting the client to accept or live with incomplete areas. Maybe a concrete pad has to be poured one year for an outdoor kitchen that will be installed the following year. Some clients may have the patience to live with this but most will not.

Having an overall vision or goal is imperative in this type of project. You can’t possibly get a client through a multi-year phased build out that is spread out over various areas without having a vision established that the client accepts and knows will be achieved. This type of client buy-in and acceptance is a key component of validation. The client has to know what to expect in any given year. They have to know what they will have and what they will have to live with from one year to the next.

I think the 3D design approach can be a very valuable tool in these cases. If your design program depicts the final result, you have a realistic 3D walkthrough that you can use to show the client during the design review. However, you can also use that design to “back track” year by year and depict what will be achieved each year and what the client will be living with until the next year’s work is completed. Within the 3D design software, you begin working backwards to show the state of the space at the end of each year’s work. Once you have all of the separate year-by-year states you set them up sequentially to walk the client through them one by one during the design review. These should be set up to show everything that is complete at the end of that year and how it will look. The example I mentioned before of a pad for an outdoor kitchen can be shown in a phase design review as just what it is, a plain concrete slab. However, you have the ability within 3D design software to show what the client could do with that space; add some pots, place the gas grill in the space, place a table and chairs, etc. In other words, you show the client how they can survive and live with the space in a temporary state.

The design work increases because you have to show the client what they will have each year and what they can do with it. Sometimes, the work is of a nature where the temporary results are just beyond improvement. Putting in a pool for example often requires considerable time before the pool deck can be installed. A client has to accept some period of “under construction” within the space in order to achieve their goal. No amount of 3D modeling or any other design depiction is going to change that.

I think much of the traditional approach where areas are built out one at a time, is a result of two things. First, it is obviously an easier approach for the designer and in many ways easier on the client. However, a large part of the issue may be impatience on the part of clients and secondly a much easier economy than we have now. If a client had $80K to spend on their backyard and front yard over two years in the past, they may have simply opted to spend $60K up front for the backyard and $20K in year two for the front yard. In today’s economy that may not happen.

A more creative approach to allocating money within a budget that meets long-term goals over time is necessary. Being able to show clients that their needs will be met over time is also necessary. A new economy requires a new approach. Validation is important but being able to show how that validated need will be met in multi-year project phases is crucial. Selling the approach through creatively showing the client how they can live through a multi-year project is a key skill in surviving as a designer when clients are being more conscious of how they are spending their budget. Being able to creatively show clients how they can be budget conscious and still meet their goals is a real asset in today’s economy. 3D visualization and validation are key components of that capability.

The Client Priorities Dilemma

August 10, 2010

Setting priorities with a client can be very difficult. You not only face indecision but also intra-family squabbles over what is important. There are many ways to consider priority. You can look at is from the standpoint of importance to the client, severity of necessary repairs and maintenance, costs, value created, ease of implementing, and a variety of other perspectives.

What it really comes down to is for you to pick the major criteria and work with the client to have them make choices. Choosing can be painful for the client. Not only the stress of actually choosing but the “buyer’s remorse” after the choice is made. In addition, as I will point out below, clients have to make tough choices about short-term wants and long term needs.

I find it is sometimes easier to identify all of the needs and then look at what the prioritization criteria could be for each one. Assume the list of things needed is as follows:

- Patio / entertaining area

- Outdoor kitchen

- Pergola

- Built in gas firepit

- Perimeter planting / screening

- Drainage issues near residence

- Existing trees cutback / trim / fertilize / maintenance

- Existing beds cleanup / replant / mulch

You could go through this list and create prioritization categories such as:

- Cost

- Value created

- Client importance

- Long term maintenance issue

- Appearance improvement

What you would end up with is a table such as this where the X’s represent a criteria for that item:

| Cost | Value created | Client importance | Long term maintenance issue | Appearance improvement | |

| Patio / entertaining area | X | X | X | X | |

| Outdoor kitchen | X | X | |||

| Pergola | X | ||||

| Built in gas firepit | X | X | |||

| Perimeter planting / screening | X | X | X | ||

| Drainage issues near house | X | X | |||

| Existing trees cutback / trim / fertilize / maintenance | X | X | |||

| Existing beds cleanup / replant / mulch | X | X | X |

There are a couple of points to consider. First, there are probably too many criteria for a client to consider at one time. One approach would be to simplify by prioritizing based on cost, assuming the client has a limited budget. If the total necessary work is $70,000 and the client only wants to spend $30,000, that would seem to be the quick way to prioritize. However, that approach doesn’t give the client the benefit of knowing what all the issues are. There may be items that create value for a low cost that they might disregard if they don’t know that criteria. Similarly, some items may create long-term maintenance (and associated cost) issues if they are not dealt with now.

The second issue is what I call “wants versus needs”. A client may want an outdoor kitchen, but do they really need it. If they know that getting an outdoor kitchen may cost them thousands of dollars in structural repairs because they decided against dealing with drainage issues, they may think again about priorities.

This is really where you get into the heart of analysis. There are no quick and dirty rules. You have to look at the list of things that are wanted and things that are needed. You then have to decide on what the criteria are that should be used to prioritize them. Based on that, you need to decide what are the most important criteria to present to the client. If you just want to sell your services, you give the client what they want and forget the rest. If you want a long-term relationship, you help the client decide the best way to allocate their budget to meet their goals and protect the value of their investment in their home.

The Features / Functions / Benefits Approach

August 4, 2010

Years ago, I knew a person who was going through sales training for a major computer company. They used an approach called feature/function/benefit selling. In this approach you talked about the products features (what it has), functions (what it does), and benefits (why it is important). I am going to use a built in gas fire pit as an example.

At a micro level, the gas fire pit has many features, functions, and benefits. Here are just a few examples:

| Feature | Function | Benefit |

| Runs on natural gas | Always available | No tanks to replace or refill |

| Clean | No debris or ash to clean up | |

| No smoke | ||

| Electronic ignition | One button to turn on | Easy to use |

| Wire mesh cover | Keeps out debris | Ease of maintenance |

| Safety | Prevents accidents |

As you can see, features can have more than one function and functions can have more than one benefit.

As designers, we don’t often delve into the micro level. Let’s look at the gas firepit from the macro level. What are the features, functions, and benefits of having it as part of the design solution?

| Feature | Function | Benefit |

| Fire | Creates ambience | Provides subtle lighting |

| Establishes a gathering place | ||

| Provides warmth | Makes cool evenings more comfortable | |

| Extends outdoor season | ||

| Built In | Safety | Cannot be accidentally toppled |

| Natural gas fuel | Ease of use and maintenance | |

| Integrated into patio | Looks like a natural extension of the space |

I have used the feature / function / benefit approach in a number of proposals and client presentations. It is a great way to convey to the customer the benefits your product or service offering provides. It justifies the benefits by tying them to specific functions and features. The most difficult part is developing the three distinct components. Features often overlap or are very similar to functions and functions often overlap or are very similar to benefits.

There are three reasons for bringing up the features / functions / benefits approach. First, it can be useful in a design review or a client presentation. It is a great tool to use to talk through your design explaining how specific features provide functions that provide benefits. Second, it is very closely related to the design process. When you are designing something, you have to look at it from the other direction. What benefits do you want to create in your design? What functions will provide those benefits? What features do you include to provide those functions?

The table below shows how feature / function / benefit analysis ties into Client Interaction and the Design Process:

| Client Interaction | Design Process | |

| Feature | What the client asks for | Client interview and observation |

| Function | How the client intends to use it | Client / site analysis |

| Benefit | Why it is important to the client | Design solution |

When we get to the point of developing design solutions, we should be addressing how we are going to benefit the client by providing a space that meets their needs, provides the outdoor experience that want, and is aesthetically pleasing. During the client interview stage, we are learning what the client wants. Clients usually ask for features. They want entertaining space or comfortable seating areas. They are seldom asking for benefits. That information is what we use to determine the functions we need to provide. We do this during the client analysis and site analysis. Creating or developing our design solution is where we translate the features and functions into benefits for the client.

The third reason for bringing up the feature / function / benefit approach is that it also supports the validation concept. Being able to trace benefits in the design solution back through the functions that were developed through analysis and then back to the clients feature requests is an excellent validation method. You get the added benefit of having a ready-made template of features, functions, and benefits for your client presentation.

Working with the Utilization Matrix – Part 2

August 1, 2010

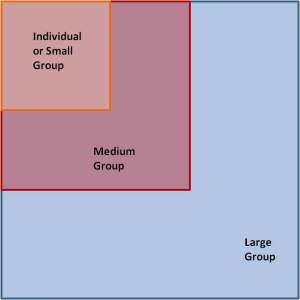

In part one of this series I discussed getting the client to identify usage ranges; upper and lower limits of how many people might be involved in various uses of the space. As a way to validate that data, I pointed out that you could count the X’s across and down. Counting across gives a tally for each use. Counting down gives a tally for each user or group of users. Those two sets of data gave us a starting point for considering the potential consolidation of spaces to serve multiple needs. The diagram below is the result of where we are at this point.

I mentioned prioritization and space requirements as two likely next steps. Let’s look at space requirements first. We have an upper and lower range for number of people for each function. Using twenty-five square feet per person and a guide, we can calculate the average space requirement per use. The graphic below shows our utilization matrix updated with the average square footage required by use.

There are a couple of things to keep in mind. First, the active play area may not work well using a twenty-five square foot rule of thumb and an average usage. We probably should find out what “active play” means and how much space the client thinks is appropriate rather than apply a formula (I am going to assume at this point the client wants at 20 by 40 square foot area for children’s play area). Second, averages don’t always work well. This is especially true in the smaller areas. The uses at the bottom of the list happen to be the uses that have the highest frequency; one, two, or three times per week. We should probably use the upper limit for as a guideline for those spaces since they occur often and there are quite a few of them. Making some adjustments, we have a new Space Needed column with adjusted square footages:

This creates an interesting new way to layer the usage as shown below:

Allocating a specific amount of space to active play and using the upper limit of users for space requirements increases the space requirements per use but there is one important factor to keep in mind. These spaces can serve more than one purpose in most cases. Just because an area is set aside for sunning does not mean it cannot be used for space during a summer party with the neighbors. The spaces overlap both in purpose and in reality as shown in the graphic below:

The question is if the active play area will be separate or will it overlap and serve as some of the overflow area for large groups:

We need at least 750 square feet for the combined group areas and 800 square feet for the active play area. If the clients have that much space available, there really isn’t a need to prioritize from a space standpoint. However, if space is limited, the client will need to prioritize and make decisions about how important that play space is and can it serve a dual purpose. The point is, the utilization matrix gives us an analysis framework, but we still need to work through specifics with the client. Those specifics include priorities and granular detail about the uses and users of the space. It may be that the client’s definition of a large group includes many children. In a large group event, those children would use the active play area, which would reduce the demand for the remaining necessary large group space. Those are the details you have to get from the client, understand, and work into your space utilization analysis.

Keep in mind that there may be other reasons to prioritize. Budget may be one of them. That being the case, you could go through the same exercise and add a column for budgeted cost per use. Any other criteria can be used to sort, group, or expand the utilization matrix. There may be other criteria you want to consider. Some examples include: distance from the residence, exposure to sun, need for privacy, noise, etc. The graphic below shows the utilization matrix updated for usage by time of day:

This expanded matrix above may gives us ideas about requirements for lighting. In may also provide insight into space positioning to either take advantage of the sun during the day or shade during the afternoon and early evening. Any particular variation of the matrix expanded for some particular type of data may give you insight into an issue or factor you need to consider in your design. Looking at a variety of issues may indicate conflicts that require the client to again prioritize what is most important to them. For example, creating sunning area may use space that is significant for other uses that require shade. The client has to decide how important that sunning area is versus forgoing comfort is other usage situations.

As you may have gathered, this utilization matrix was created in Microsoft Excel. Once the basic matrix is complete, it is a simple matter to copy the worksheet tab to create a new or modified version of the original. You can reuse your original matrix as many times as necessary to analyze all of the factors you think are important or crucial for the project.

The utilization matrix raises questions. That is a good thing because it gives you the opportunity to get clarification from your client. It also gives you information about relationships between how the space will be used and who is using within different contexts. It may provide insight into how space adjacency should be applied. There may also be insights into specific issues such as where you need to consider lighting, screening, and other design elements.

As with many other tools I have mentioned, a utilization matrix really only makes sense on projects of a certain scale. However, once you hit that point, it can be extremely useful is sorting out how the client wants to use the space versus what you need to design to meet that need. Once you have the basic structure of uses and usage it is easy to expand the matrix to evaluate other issues.

Working with the Utilization Matrix – Part 1

July 20, 2010

Once I have gathered both sets of data for my utilization matrix, my next step is to get the client to approximate how many people are involved in the group functions. I usually ask the client to give me a range. The result gives you a lower and upper limit of how many people are involved in each activity. I also ask about frequency; how often does this activity occur. A sample is shown below:

It is clear that the special events and parties involve many more guests, which imply the need for overflow space. These events do not occur very often; six per season. In this case, season means May to September. The next largest requirements to accommodate guests are children’s activities and entertaining. The chart below shows the uses sorted and grouped:

Another way to evaluate this information is to tally the number of items in each Use (row) and for each User (column). That tally is shown below:

It is clear looking at the column totals that the husband, wife, and children drive the needs. This is expected. Gatherings with close neighbors and in-laws are the second largest group of drivers. Also expected is the uses with the largest number of users are the special events and parties.

There are opportunities at this point to start looking for potential ways to combine spaces to serve multiple needs. The chart below adds a series of columns to the right that show some potential groupings of spaces:

Some of these groupings may make a lot of sense and may be incorporated into the final design. However, before going any further there some other things we should be looking at and considering. One is the client’s priorities. Another is space requirements. In my next post, I will use this same utilization matrix to begin looking at those two issues.

Developing a Utilization Matrix

July 15, 2010

Getting a client to articulate how they want to use their space can be a challenge. However, if you can get them to really think about it and dig into what they currently do and would like to do, you can get a very substantial list of functional requirements. Assume you spend thirty minutes questioning the client and getting them to really think about all the ways they use their backyard and would like to use it in the future. You might get a list of uses like this:

- Read paper w/ coffee in morning

- Relax with glass of wine

- Evening by fire pit

- Family BBQ

- BBQ with close neighbors

- Summer party with neighbors

- Special events with extended family

- Special events (i.e. party)

- Entertain in-laws

- Play games / active play

- Play cards / board games

- Hang out with school / team friends

- Read and relax

- Light gardening

- Sunning

- Children team party

- Maintenance / upkeep

If you can get a substantial list like this, you are far ahead. The question that remains is who is using the space during these activities. This also requires the client to carefully think about each activity and determine who is involved and how many family members, relatives, guests, etc. are typically part of that activity.

You might end up with a list of participants such as this:

- Husband

- Wife

- Older children (13+)

- Younger Children

- Close Neighbors

- Other Neighbors

- In-Laws

- Extended Family

- Children’s Friends

- Children’s Friends Parents

You can use these results to create a utilization matrix that combines both of these sets of data; what and who. You should end up with something like this:

A matrix like this gives you a lot of data and a lot of opportunity for analysis. Each intersection point with an X marks a required need that must be met for one or more of the users. At this point, we do not know how many people are involved in these activities so it is hard to evaluate the scale of the needs. We do have some sense of the range of activities and where some the priorities are. Also, remember that the client (husband and wife and children) are really the drivers. All other users are invited, occasional users. That has an impact on priorities.

The table of X indicators can be sorted or rearranged in different ways to glean some meaning out of the pattern of X’s. This may help in subsequent analysis.

One obvious step would be to look for opportunities to consolidate some of these activities into common spaces. The fire pit area could serve a dual purpose as an intimate seating area. The active play area could provide overflow space for large gatherings. There are opportunities to create spaces that serve more than one purpose. More analysis can help make those determinations.

The client may be asking for more than the space can physically accommodate. In that case, this matrix can be used as a tool for the client to make decisions about importance or priorities. Tallying the number of X’s in the table for each need and for each group of users will give you some sense of importance and scale. However, those tallies are not precise measures. Graphing some of the data may help in the analysis and may help uncover some patterns in the data.

My next couple of posts will deal with further analysis of this matrix. Some of the techniques mentioned above will be explored in more detail along with some other types of analysis.

Prototypes in Landscape Design – Final Thoughts

July 12, 2010

A few final wrap up comments about applying prototyping to landscape design. These comments and observations are mostly things I have carried over from my prototyping experiences in the systems field.

Getting client requirements is crucial. Having a design methodology with an approach to gathering requirements is extremely important but probably more important is having a toolkit of methods and approaches you can apply in different circumstances. One size does not fit all in design methodologies. The major thing to keep in mind is that you must gather all client requirements, gather them completely, and gather them accurately. Finding the mix of tools and approaches that will allow you to accomplish this comes with experience and practice.

I would not tell a client I am going to prototype their design or some portion of their design. However, I would use a prototyping approach if it was appropriate and it would allow me to draw out and/or confirm some of the client’s needs. If I was doing a physical representation with stakes, cord, boxes, and other materials, I might describe it as a walkthrough or simulation. The approach is the same; I just am not bogged down in the use of the term prototype.

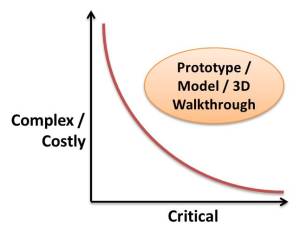

As I said in an earlier post, almost everything we create to represent the client’s design is a prototype. These artifacts just have different levels of visual and functional fidelity. A simple plan view is a prototype. If I can use that plan view to validate the client’s requirements there is no reason to go further. However, if the client continues to waver or expresses concerns, I may have to dig into my toolbox and apply a creative approach to representing the design that will communicate the design intent and how it meets the client’s needs.

Some prototyping can be done with either 2D or 3D design software. Other prototypes may be visually enhanced photos. Physical models take time and talent but, if you know what you are doing and are good at it, giving the client a scale model can be impressive. Simulating areas and/or spaces with objects, lines, and other materials is a good way to give the client a sense of space and proportion. The point is you need to determine what you need to convey, how much fidelity you need, and the best way to convey it.

Having the right tools and knowing which tool to use is important. In addition to DynaSCAPE, VizTerra, DesignWare, and other landscape design packages I use other tools to augment my design analysis and presentations. Software such as PowerPoint, Excel, Work, Visio, Photoshop and others allow me to produce analytic materials and client presentation materials. They can play a role in prototyping if they allow you to create a representation you can use to convey what you need. I typically use the tool that will work best for what I need to accomplish whether it be analysis, design, or creating a prototype. However, I always keep in mind how I might be able to leverage that material later in the project.

Making the choice to use physical representations with rope, cord, hose, stakes, boxes, etc. is a little more difficult. Deciding when to use physical representation is primarily a matter of experience and ability to read what the client needs. There are clients who just cannot visualize anything. Even with a plan view, enhanced digital photos, drawings/sketches, and other representations, they just cannot sense or visualize how it will work, how much space will be available, etc. In some cases, you might decide to use a physical representation in order to convince the client that their ideas will not work or you want to show them an alternative approach. Whatever the motivation for a physical representation, you need to decide how much effort to put into it to create the level of functional or visual fidelity to meet your needs.

Prototypes do work. The key is to use the right tool or technique at the right time for the project.

Applying Prototyping in Landscape Design

July 6, 2010

My last two posts have dealt with prototypes. Prototypes are representations of the design objective or some portion of the design objective. That being said, almost everything we create to show the client as landscape designers qualifies as a prototype.

In my first post on this topic, I mentioned that I have been a big proponent of prototypes for many years. However, this was in the context of information systems. I did not see an immediate fit for prototypes within landscape design. In thinking about prototyping from the standpoint of how they are used and their varying levels of fidelity, I think the prototyping approach is actually used within the landscape design field. It just may not be used consciously. Let’s look at some examples.

First, assume you get a call from a homeowner who wants a consultation on what is feasible in their backyard. They have limited space. They would really like a pool but they need a deck or patio for entertaining. They just don’t see how it could work. Assume you meet with the client, make some measurements, and evaluate the space. Since this is a simple consultation, you grab your note pad and sketch out a rough diagram of the space. You use bubble diagrams to show how the functional areas, the pool and the entertaining space, could fit into their yard. That hand sketch is a prototype. You are using it as a proof of concept. It has zero functional fidelity and very low visual fidelity but if it convinces the client, it did the job.

In our second example, you are designing a front yard walkway. The clients want to enhance the curb appeal of their home. Their current entry way is obscured and offers visitors no clue of how to get to the front door. You take measurements, get the budget, and get other information from the client. You create a colorize plan view showing the new front yard bedding and walkway with all new hardscape and plantings. That plan view is also a prototype. It has high visual fidelity in that it is colorized and shows the flow of the walkway and how it is visible from the street. It has some functional fidelity in that it shows how it functions by opening up the view from the street. However, it is not high fidelity because the clients have to translate from a 2D drawing to how it will look when it is actually done.

In this last example, you have already sold a design. You are creating an outdoor entertaining area with a large fireplace at the end of the patio. During the design phase there was a lot of discussion about size and cost tradeoffs and the client made their decisions about how much space they were willing to pay for. Construction has begun. The patio area is dug out. The concrete will be poured in a couple of days. After that, the construction of the fireplace area will begin which includes side benches for seating. The client calls in a panic and says they just do not see how it will fit. They are very concerned about how the fireplace and seating will fit and that there may not be enough space. Realizing the problem is one of visualization you go to a store and get several cardboard boxes. You go to the client’s home to meet with them. You grab the cardboard boxes and set them up, one on top of another, to represent the fireplace and side benches. You move the client’s outdoor table into a position to represent how it might be set up after construction. The client can then see a physical object where their fireplace and seating are going to be located and how a table and chairs fit into it. This leads to some discussion and playing around with the space. The client decides they really want more space. They are willing to reduce some of the other yard areas to get it. They can afford the change and ask you to have the contractor push the fireplace back two feet. They realize it is their decision and are willing to pay the additional cost and suffer the delay. Those cardboard boxes were a prototype. It had very low visual fidelity but moderate functional fidelity from the standpoint that the represented the scale of the objects.

Each of these examples shows how a different representation was used as a prototype. The first two, the quick sketch of a bubble diagram and the colorized plan view are very common in landscape design. Using cardboard boxes to represent hardscape is less traditional. In each case, the degree of visual and functional fidelity varied but was adequate to achieve the objective.

In the first case, you could have taken the client’s information and gone back to the office to create a plan view drawing to show how there was adequate space for the client to achieve their objectives. There may be cases where you have to do this to convince the client. Some client’s want more detail or want more precise drawings. You have to judge the client and determine what will work for the client and your objective.

In the second example, there are other approaches that could have been taken. You probably would make the plan view drawing anyway. Colorizing it was an enhancement that may or may not have been necessary. The plan view would show how the space was opened up and how the new walkway was more clearly defined. Colorizing just adds to the visual fidelity in that it shows space relationships between hardscape and softscape more clearly. It may also show the client how you are working in their preferred color scheme. There may be cases where the client just cannot make the 2D to 3D translation and creating a 3D walkthrough may be necessary. This is again something you have to determine for each client and project.

In the last example, objects were used to represent hardscape objects within the design. You may be need to get creative when you to try to physically model something. Sheets, plastic sheeting, or large sheets of brown wrapping paper can be used to represent walls or fences. They can also be laid out to represent walkways. A trash can may be used to represent a water feature. Hose or cord can be laid out to represent bedding edges. There are endless possibilities. You just have to determine which design elements you need to represent and then what you can use to represent them.

All of these examples of prototyping also demonstrate how prototyping can be applied at different stages of a project. In the first example, it was used as a proof of concept. The second example showed how it was used to convey the design result. The third example showed how prototyping can clarify issues and/or determine if changes are needed during construction.

None of the examples dealt with prototyping as a means of facilitating requirements gathering. This is probably one of the most useful applications of prototyping. Being able to show clients a prototype representation of some portion of their design may help the client clarify what they want and allow the designer to explore ideas that the client has not expressly stated. What you prototype and how you prototype really depends on what you are trying to accomplish. Prototyping can answer questions.

Bringing in stakes and cord to mark off different functional areas can help the client understand how their new space will be proportioned and how it will flow. If there are questions about how confining a fence or wall will be, one approach might be to hang clear plastic sheeting in one area and a more solid material in another to give the client a sense of how different materials can provide varying degrees of transparency. That same question might apply to the fence itself. Placing some plant materials in front of a sheet to represent how the fence is obscured may convince the client that the fence will be a good functional element but it can be made visually attractive though the addition of plant materials.

There are many, many opportunities to use a prototyping approach in landscape design. I realize I am using a very loose definition of prototyping. In other design disciplines, prototyping is more of a way of approaching a problem. It is not necessarily any one tool or set of tools.

In landscape design, prototyping can be both an approach and a tool. I have frequently recommended that client contact and feedback be a priority throughout the project. This provides opportunity to show the client small prototype components of the design. Getting client concurrence early in the project and often, helps prevent costly redesigns. As the project moves along, designers should keep prototyping in mind as a useful tool to help clarify issues or develop understanding of the design intent. More importantly though, the prototyping approach can provide validation of both overall design concepts and specific design elements.

How and When to Use a Prototype

July 5, 2010

Prototyping is a technique used in design, in many different disciplines. The term is seldom used in the context of landscape design. In other design disciplines, prototyping can be used to:

- Show a proof of concept

- Gather requirements

- Validate requirements

- Explore solutions or resolve specific design issues